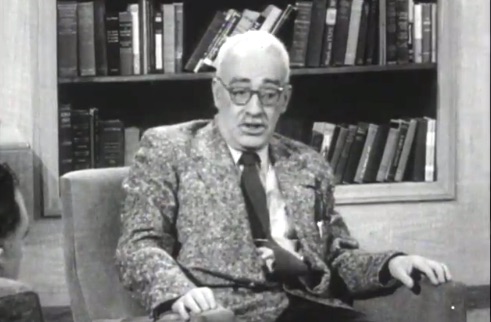

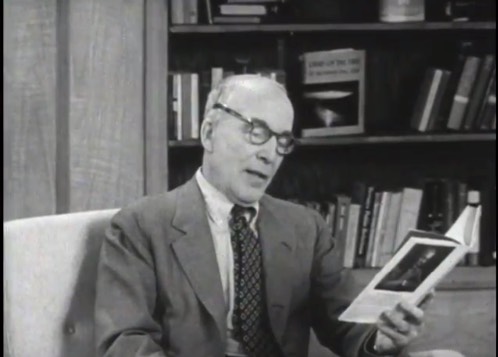

Walter Kerr interviews Frank O'Connor.

Writers of Today: Robert Penn Warren

- Description

- Reviews

- Citation

- Cataloging

- Transcript

If you are not affiliated with a college or university, and are interested in watching this film, please register as an individual and login to rent this film. Already registered? Login to rent this film.

Each volume of WRITERS OF TODAY is a dialogue between noted literary critic Walter Kerr and one of the best known writers of our time. Produced in the 1950s, these programs provide rare profiles of these men as they discuss contemporary literature and society at the time of their own writing peaks.

Robert Penn Warren focuses on the creative process of writing. He discusses with Kerr the search for Identity which is ubiquitous in his novels and poems as a metaphor for writing itself. The fundamentals of fiction - place, characters, story - are also discussed, but Warren insists that without an innate 'germ,' one cannot simply learn mechanics and become a writer. Asked about his students, Warren says it is too often true that 'they want it quick and easy.'

Citation

Main credits

Kerr, Walter (Host)

Distributor subjects

No distributor subjects provided.Keywords

Writers of Today: Robert Penn Warren

[00:00:10.76] Writers of Today, one of a series of programs about the role of the writer as thinker and creative artist. Today's guest is the distinguished American novelist, poet, and teacher Robert Penn Warren. Joining in the discussion and appearing as interviewer in this series is Walter Kerr, playwright and drama critic of the New York Herald Tribune.

[00:00:39.91] This is Mr. Robert Penn Warren, who is not only the author of a number of distinguished novels, All the King's Men, Band of Angels, World Enough and Time among them, but in addition has produced a considerable body of poetry, who has worked in the theater, written several plays, and who still finds time to teach. In fact, he gives about half of his year to teaching, in part to the teaching of writing and play-writing. And I'd like to ask Mr. Warren if there is any one common difficulty he finds among his beginning students in writing. Is there one thing, one question they come to you with?

[00:01:20.94] Well, the most human question I guess they want it quick and easy. They want a formula. They want an answer in the back of the book. And they have come to the wrong place, I guess.

[00:01:32.77] Well, do you mean this in a mechanical sense, that is to say they're really looking for some kind of automatic shape, a kind of die press that they can stamp onto their work or fit their work into?

[00:01:43.53] I suppose they think there's some sort of secret you can learn. And I guess we all want a secret that's going to make us wiser, richer, better at something.

[00:01:53.99] I suppose in a way you can't really blame them.

[00:01:56.12] I don't blame them a bit. I'm hunting it too.

[00:01:58.83] Yeah.

[00:01:59.82] I just haven't found it.

[00:02:00.46] I see.

[00:02:01.10] Do you think a good writer ever does find such a formula, a good writer now?

[00:02:04.35] I should doubt it.

[00:02:05.89] In other words, he is always, always changing in the course of his work so that each new work is a new experience.

[00:02:12.02] Wouldn't you guess that?

[00:02:13.06] I suppose it is. I suppose some writers do find formulas, but that they die the moment they hit them.

[00:02:19.51] The moment they hit self-imitation.

[00:02:20.63] Yes.

[00:02:22.39] That's I suppose the most fatal of all things.

[00:02:24.34] Is that a special vice in our time, self-imitation?

[00:02:28.64] I guess it is. This reason, if a thing works, it ought to work again. And all the pressure of salesmanship and promotion and ordinary human desire for easy living is in favor of doing the same thing over because it worked.

[00:02:45.37] Yes. I was once on a symposium at Harvard. And I heard someone say that. He talked about, I think, in terms of early success, that is to say, one really successful novel, one really successful play, and you're lifted so far above the apprentice stage in an instant.

[00:03:00.16] Yes.

[00:03:00.42] That then you step out of it, feel you never can go back to it, stop apprenticing yourself, and therefore do become set.

[00:03:08.04] Can't start over again. I suppose in a real way, it starts over again every time he starts. He knows a lot of things or thinks he knows a lot of things. But they are not any real use to him, the new job. You have to really re-apply them in some fresh way.

[00:03:22.96] Is there something, though, that you can teach the student when he comes to you? What is the purpose of his being there, would you say? Mostly to shock them into this awareness that he's got to find it out for himself?

[00:03:33.72] I don't know, really. I honestly don't know why he's there at all. Or why I am, to tell you the truth?

[00:03:38.72] Well now, you've got to have some reason.

[00:03:41.10] Well, some sort of a-- I wasn't wholly kidding. No. The reason is this, I guess, the Yeats remark, "there's no school but the singing school of the soul." In fact, the other writers, they're given to the past. Once you can look at them and try to see what kind of world they came of and what kind of works they made out of that world, then you have some sort of a sense of the relation between the materials of life and the book, the poem, they play, whatever it is.

[00:04:15.72] In other words, there ought to be a kind of osmosis there that they soak up it.

[00:04:19.01] Just by osmosis, I should think.

[00:04:20.47] I see. Well, now supposing that there is no formula, supposing there is nothing terribly concrete or technical that they can learn, what can be their point of departure in beginning a work? If every work is going to be a work of exploration, of even finding the materials as you're writing the materials, am I wrong in supposing that's in part what you mean?

[00:04:40.64] Yes. That's in part what I mean.

[00:04:42.14] You're finding them as you go along.

[00:04:43.48] As you go along, yes. You're finding your meanings as you go along.

[00:04:45.92] Your meanings. I see. Well, what about just getting the seed to get it going? What about the first point of departure? Is there one?

[00:04:51.78] If a person doesn't have that germ, the interesting phrase he starts with or the episode he starts with or the idea he starts with, you can't give it to him, because you can't give it to yourself.

[00:05:03.28] That's part of the innate aesthetic equipment, to use a bad word.

[00:05:08.81] Sure. If nothing fires him up, nobody can fire him up.

[00:05:11.84] I see. And once it's fired him up, then he's simply got to go out of his own and--

[00:05:15.33] On his own. On his own.

[00:05:16.30] And find his own way through it in some way.

[00:05:19.32] I say this role of his friends-- and that's what you are, presumably. You're taking the place of the friends of the author if you're in school with him or running a class or something. You're trying to sharpen his own critical powers, his powers of self-criticism. You're just nagging him in a way he ought to nag himself.

[00:05:40.47] I see. And beating him up regularly, I suppose.

[00:05:43.33] Regularly. Now, you were in this business for seven, eight years. What did you do?

[00:05:48.00] Well, I quit.

[00:05:49.36] Right. You quit. Right. You quit.

[00:05:52.39] I do think there are certain obvious mechanics you can teach a man. But if that's all he ever learns, it's going to be a dead thing from the beginning. There's nothing-- you might be able to help him, teach him a few shortcuts provided he has the basic material to begin with. And that you can never control, can never really even change or shape, I don't think.

[00:06:10.06] Well, this business now of starting from some kind of point of departure, everybody starts from a germ, as you say, from some kind of seed that he's got innately in him. I suppose that could be almost anything. In other words, even, oh, a factual record or a scene, a place that someone has seen at one time or another, all of these things might generate this, the beginning, the embryo of a novel?

[00:06:31.03] I should think so. I once heard Thomas Wolfe say he was going to write a book about October, just about October, about leaves in the streets. And so I said, what about the story? He said, well, I haven't thought about this, but it's about October.

[00:06:45.55] Did he write the book?

[00:06:46.89] I guess he did. It could apply to several of his books.

[00:06:50.51] Well, I guess one reason I really asked that last question about could a place or something of that kind be a starting point is because I notice that in your own work, the sense of place is terribly strong. And I've often wondered whether or not place is a kind of germinal thing with you. Is it? Or would you say not?

[00:07:09.33] It was in one novel. The novel was so bad it never got published.

[00:07:12.94] Oh.

[00:07:14.46] So I can't recommend that.

[00:07:15.89] You don't recommend that process.

[00:07:16.88] On personal grounds, no.

[00:07:17.93] Still, you've carried your sense of place right along with you into the other novels so that it is extremely vivid. I may be wrong about this. I don't want to put myself in the place of an analyst.

[00:07:27.06] But I just keep feeling so often in your work that first, at least I as a reader, come to sense the place. And then out of the place, I come to sense the character. And out of that, I come to sense what is going. But so often I seem to begin as a reader in terms of place. But you don't think that as a writer you deliberately--

[00:07:45.52] Not deliberately, no. If it's true, it's true without my being aware of it. Certain kinds of places I think have almost metaphorical values, and that the sense of setting is a sense of emotional waiting, of anything that happens in that place, that carries that quality. But that's as far as I would go.

[00:08:06.33] I see. I know I happen-- for instance, in re-reading Brother to Dragons, which is, of course, your long narrative poem, or you call it a tale in verse and voices, one of the earliest things in it, one of the things that struck me most was again, I think not a major step for you in this particular work, but still to me had such a strong sense of place that I sort of felt your idea germinating. Now you tell me perhaps it didn't work that way. Would you mind very much if I read you a little portion here? I'll ruin it for you.

[00:08:37.15] Read it to me. Let's ruin it together.

[00:08:38.76] All right. OK.

[00:08:39.51] I've done my best to ruin it already.

[00:08:41.32] It's quite close to the beginning of the whole thing. You're writing here in the first person. You're writing of yourself in part of your own journey back to the Kentucky country.

[00:08:52.63] You're looking for a house that you know has burned down, a house in which a very violent act occurred. You're on your way up a hillside. You're re-exploring the country.

[00:09:01.03] Yes. And you won't believe it, but the man really said.

[00:09:04.38] Oh, he really said these things.

[00:09:05.25] Yeah. It's not made up.

[00:09:06.27] I see.

[00:09:06.89] [INAUDIBLE], it's true.

[00:09:07.82] Oh, well, truth, then. As you come up to this-- to a little house at the foot of the hill and you want permission to go up and explore the territory, you go on something like this.

[00:09:20.20] "The present owner's name is Boyle, Jack Boyle, so the mailbox said outside the white-washed fence. The house was white, a tidy bungalow. The roof was tin and blazing in the sun and zinnias blazed in the one flowerbed. A fat old collie panted in the shade.

[00:09:37.35] I knocked and waited there for Mr. Boyle to come and tell me I could climb the mountain. 'Sure can,' he said, 'if you ain't got good sense, a day like this and all that brush to fight,' and said again more heartily, 'sure can. Sure can. But when you get up there on top, just one thing, please. Just please don't go and bother my rattlesnakes I'm fattenin' up for fall.'

[00:09:59.52] Oh, he was quaint or cute was Mr. Boyle, or could be made to seem so. But Boyle's not quaint because he speaks the tongue his father spake and holds his manners yet. Or if he's quaint, he's quaint only as a man of moderate circumstances, modest hopes, and decent ambitions. And he did his best, mortgage and weather taken to account, and minor irritations flesh is heir to, will do his best, no doubt, until he dies, if he's not dead already, caught the flu, fallen off his tractor in the sun, or had a coronary hit him on the street down in Paducah where he'd gone to trade.

[00:10:37.53] He's gone. And a world's thus dead and gone beyond me. And part of the world that's dead is I myself, for I was his creation too, that fleeting moment I blocked his doorway and he stared at me, a fellow of 40, a stranger and a fool, redheaded, freckled, lean, a little stooped, who yearned to be understood, to make communication, to touch the ironic immensity of afternoon with meaning, to find and know my name and make it heard while the sun insanely screamed out all it knew, it's one wild word, light, light, light. And all identity tottered to that remorseless vibration.

[00:11:19.13] I thanked him, turned away, got in my car, and left myself dead on his porch. And he went to his house, to the shuttered cool, and left me dead forever."

[00:11:34.86] Now, that at least illustrates what I was trying to talk about, that is to say, I begin with a place as a reader. And out of the place comes a man. And out of the place comes another man, yourself. And out of the two men and the place comes an idea, an idea finally.

[00:11:49.56] That's a fair account, actually, of what happened. It was a place. It was a particular place, but not thought of that way. I was merely trying to get permission to go up on the hill.

[00:12:00.37] And at what point did the idea come out of this?

[00:12:06.26] Stage by stage. I was halfway through the passage, I recall, before the notion of the passage developed.

[00:12:13.13] I see. In other words, you may have begun simply as a descriptive thing.

[00:12:16.38] Again, it's just an account of getting permission, descriptively. And then by a little, it developed. One thing led to another.

[00:12:24.80] Yes. And the idea of the mutual death, of that moment, the mutual death of part of both of you in that moment in your relationship there is something that simply grew from the--

[00:12:36.16] It grew from it, yes. It grew from it in a context of other things that I had already thought about the poem, though. And I guess this leads us to something.

[00:12:45.12] Yes?

[00:12:46.35] That is, I did know what the poem was going to involve, a problem of identity in one way or another later on.

[00:12:53.63] That's the next question I was going to ask you. In other words.

[00:12:55.94] You were setting that up there, is that it?

[00:12:57.89] Well, I was. And then we got there.

[00:12:58.86] All right. Well, I anticipate you then. Well, I'll say what I started to say anyway.

[00:13:04.60] Please.

[00:13:05.58] And just this. That the poem, the story of the poem, there's this monstrous fella Lilburne, the bad brother, and the good, stupid, younger brother, who is the victim in a way of his older, strong, well, pathological brother.

[00:13:27.18] Now neither of these two brothers has a properly speaking identity in the end. Lilburne is pathological and therefore is not a person. Ultimately he's a monster. And the younger brother has forfeited his full identity by becoming the victim, the creature of his big brother, the bad brother And by committing a crime which cuts him off from humanity in the end.

[00:13:53.55] So that notion of identity and the losing of identity in various ways is in the poem, as well as the notion of a good loss of identity in the poem, when you can identify yourself with the experiences of people in general, yet they are valuable ways, the notion at the very end of the poem of the speaker having been part of these various characters in a way, the partaking of general human experience. So there are those notions, which I rather over-elaborated here, I guess, now.

[00:14:25.66] Oh, not at all.

[00:14:25.93] I have to set up this other notion as a motive to get started on it.

[00:14:30.56] Yes. Well, what I was--

[00:14:31.77] Move into it.

[00:14:32.11] What I was going to ask was that, yes, the work does begin in some kind of a germinal seed. Yes, you don't have a great elaborate technical preparation in mind. You don't have your full narrative developed. But to what degree does a philosophical idea, especially a prior philosophical idea, tend to shape the structure as you move along?

[00:14:52.67] Well, I could answer it this way. The poems, of any narrative content that is, and the novels and the stories, novels with one exception, have started-- with two exceptions, and those are unpublished exceptions. They started from a story, an episode.

[00:15:15.69] A factual--

[00:15:16.16] A fact, something came from history or from observation or from something. A story was there, in little or in big, was given, in a way. The situation and again, some character, was given.

[00:15:28.90] And it might lie around with me, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10 years, until I think I see a meaning for it. A lot of interpretation for the story is not-- fiction is not a story. It's a story with a meaning, I guess. It's interpreted story.

[00:15:46.67] And there are millions of stories in the world. Every day is a story. There are millions of stories. But it's when it catches you somehow, it has a meaning.

[00:15:53.14] Yes. When it becomes coherent.

[00:15:54.30] It becomes coherent in that sense, yes.

[00:15:56.09] Yes. Well, I asked the question because I've noticed that from novel to novel, certain of these basic philosophical ideas do recur. For instance, the one you were talking about, the search for identity. You'll find certainly it's one of the main springs of World Enough and Time, in which this man is trying to be who he is, discover who he is, become who he can be, in his case with an act of violence.

[00:16:19.94] Yeah.

[00:16:20.82] It occurs again, of course, in the narrative poem Brother to Dragons. And finally, it seems to me, we come to Band of Angels and the first sentence is, "who am I?" In other words, this seems to me to be a recurring and growing strain, philosophical strain now, in your own work.

[00:16:36.23] Well now, only in the last book was it a priori.

[00:16:40.50] Only in the last one?

[00:16:41.39] Only the last one.

[00:16:41.95] In other words, this is something that you've been discovering through the process of work, is it?

[00:16:46.08] Well, yes. I mean, I'm aware of its coming into the book, of course. But not part of the original conception in any book except the last one.

[00:16:53.30] Yes. I see.

[00:16:54.65] Not the starting point. And back to the question of self-imitation, oh, I think if you begin to use a gimmick, any topic you'd be ruined.

[00:17:08.74] Yes. Well, it isn't self-imitation, however, if with each new novel the same idea is expanding, in other words, is reaching larger proportions. You'd count that fair enough, wouldn't you?

[00:17:19.34] That's fair enough, I think, because you can't avoid that, unless you change yourself.

[00:17:21.93] Yourself, yes.

[00:17:22.85] Which you can't very well do.

[00:17:25.17] Of course, I've been fascinated following this in its major and minor developments, positive and negative too. In so many cases, you've had people seeking definition by violent acts. Then of course I'm interested too, say in Brother to Dragons, to find a man who is trying to lose his definition, that is to say who is trying to lose himself. This is the case in--

[00:17:44.59] Oh, you mean the younger brother.

[00:17:45.42] The younger brother, Isham, which you were talking about, who has been in a sense the victim of his older brother and who has landed in jail and who has been wrongly released from jail. Someone has helped him simply to get out of there.

[00:17:56.55] And then he runs. I wonder if-- now, you can get your revenge here.

[00:18:00.24] All right.

[00:18:00.58] I wonder if you would read a passage--

[00:18:02.42] Sure.

[00:18:03.01] --I think would help clarify that point.

[00:18:08.11] This is after poor Isham has made has jailbreak or is let out of jail in a little town in West Kentucky and has sped away down to Tennessee and Mississippi. And he winds up at the Battle of New Orleans with Andrew Jackson's riflemen at the cotton bales. He has meanwhile killed his brother, long back, and is haunted by a sense of this guilt, a sense of being outside of the human community completely now, out of the family, out of all human contact.

[00:18:45.09] "I rode away and threw my name away. I wasn't Isham, what had killed his brother. I wasn't nothing, not nobody now, like something wind will blow or blow right through, like thistle fuzz or a scarecrow on a stick.

[00:19:02.80] I said, I'm nothing and nothing ever happened. I said, I'll ride, never have no name, and rode. And then New Orleans, and the time came on.

[00:19:17.71] So it is true, the tale the rifleman brought back and told the homefolks [INAUDIBLE] when they finished that big turkey-shoot with Andrew Jackson at the cotton bales. It wasn't like a turkey shoot back home at 40 paces, and the turkey's head is not a barn door when it bobs up quick behind the log and then is down again. And that split second is your only chance to plug your pellet where the eye had been.

[00:19:46.55] No, this was different. Andy gave the party. And any fool get a turkey here. And every turkey gobbler six feet tall and gobbling slow and putting on the green, or walking at you, red and puffed with gobbling, with drums a'gobbling too to set the time, and nary a log to duck the head behind."

[00:20:08.96] Then Isham again, "Durn fools. Durn fools, to see 'em march so pretty, with red clothes shining like a wedding was, just marching at you like they never cared you aim to kill 'em and to leave 'em lay. They march so pretty. That's what made you mad, to be so brave, like all you did was naught, and any dying you could give was nothing. They spit on it and you and keep on marching.

[00:20:37.77] It made you mad, because you knew down deep how scared you'd be if you was marching there. It made you mad. And so you laid your aim on one and take the fool and load your Betsy. Just take it easy. Counter your powder right.

[00:20:55.64] Then we were yelling at the cotton bales. I jumped up high and waved my cap and yelled. I yelled for glory, how we killed and slayed and yelling too something deep inside me, like I was back with folks a minute maybe.

[00:21:12.35] And then it hit me. Some durn fool out yonder, some last durn fool that risked his hide to do it, out there with all his kind all dead around him, takes time to load and shoot just one more time back at those cotton bales. It was me he found, right in the chest, a red-coat musket ball.

[00:21:36.52] A rifle plug like ours, it's small and true and goes in easy. Not much blood comes out. But muskets, hell. If you can hit a thing, it gives a chunk. It knocks a hole. It's messy.

[00:21:51.54] It made a mess of me. The blood came out. Somebody held my head to give me water. He looked and sudden stared and said, be durn.

[00:22:02.42] They knew me, Isham. And they named my name. Folks from back home come traveling all that way to kill some red-coats and to hold my head while I was dying. And they named my name. I died right easy while they named my name, like they forgave me, even if I killed my brother."

[00:22:29.86] In other words, this particular character is someone who has been running away from himself, in a sense hoping to lose his being, even cheat or lose his definition, and has found it anyway.

[00:22:41.82] Sure.

[00:22:42.27] He's come to it in some way.

[00:22:43.64] He's stuck with it in the end anyway.

[00:22:45.09] I see. He's stuck with. And you really feel it that way?

[00:22:48.03] And then the last moment happy in that fact, because he's restored to human community.

[00:22:53.67] I see. By finding himself.

[00:22:56.08] By finding himself.

[00:22:57.19] Yes. Well, I'd like to ask you something now. We've been talking about characters, characters in your novels and this long narrative poem. But the problem with definition may have, I suppose, larger ramifications. What about for the writer? Is there a groping toward definition for him too?

[00:23:14.05] Well, I should think that the word's good enough, I guess, for the purpose, that a write is trying to do write seriously, which is an awful word to apply to it, and not merely as an assignment of one kind or another, is trying to make the process of writing a process of learning about the world and about himself, those two things, about the relation between those two things.

[00:23:43.86] And as he goes on in the writing process, he is learning more about himself.

[00:23:47.14] That's right. He's having to dig up things out of himself and out of the world and make them make sense together, because we're just trying to make sense of experience.

[00:23:54.95] Yes. Himself as a focus of that experience.

[00:23:57.70] But it isn't always conscious. In other words, as he goes along, he may stumble on something about himself he never knew.

[00:24:01.92] Never knew, and may not even know he's found it. It's in the work. He's not up there talking about himself. He's trying to write about his people.

[00:24:08.98] Yes. Yes.

[00:24:09.69] He's trying to tell his story. But the story in someway is a more or less indirect assessment of his own experience. It's bound to be. I don't see how it could be otherwise.

[00:24:21.15] Yes.

[00:24:21.36] And making sense of that experience is what really gives his work any meaning it had, I should think. He's trying to make sense of his life, the life he sees around him.

[00:24:31.44] Yes. I've always been fascinated by that remark of WH Auden's, how can I know what I think until I see what I say, almost as though there were something half-automatic or certainly intuitive about the writing process that eventually poured out something of yourself that you hadn't really seen before. Would you go along with that or not?

[00:24:51.75] Yes. I would. I'd go along with that and add something to it or state in another way perhaps. What Wordsworth said about meaning in his poems I think can apply to any moderately good work anywhere of any literary kind or artistic kind for that matter. He said, "the meanings in my poems, I didn't put them there. But I trust that habits of meditation had so formed my mind that they'll be found there."

[00:25:23.47] It's not a matter of tacking meanings on or labels on. It's hoping that you make sense to yourself enough so that your work will make sense. And that's just between you and God.

[00:25:34.72] But it's saying that maybe the meaning is me.

[00:25:37.01] In some kind of a long range way. But [INAUDIBLE], it's about something else.

[00:25:42.12] Well, you think that after a writer has done a considerable body of work, let's say, that he does quite literally know himself better. He knows more about himself.

[00:25:49.60] I think he might, but too much-- that could be a liability, I think, if it's too schematic, too literal, and too self-centered. I think once he turned himself inward in a certain way, he's going to lose the drive to make things outward.

[00:26:06.86] I see.

[00:26:07.41] I think it's very bad to use it as a means of self-knowledge.

[00:26:13.62] Of discovering himself.

[00:26:14.65] Yeah.

[00:26:14.96] Well, that brings us really over, doesn't it, to the last question you might say. And that's the question of the reader. In other words, he must always be directed outward to the reader. Is this your feeling?

[00:26:25.22] I would say to his material, to the world of his imagination. And if he's got an imagination and got any insight of his own, he'll find readers who can respond to that imagination, insides enough like his so that they feel a community there. Through the expression, he created the outside.

[00:26:43.17] well, Now is there a process for the reader that's at all similar? In other words, again, is there a working toward definition? Is there an exploratory process for the reader do you think, too?

[00:26:52.02] I don't see the difference between the reader and the writer on this, actually. That is, any sensible person is trying to make sense of an experience, of the world around, his relation to it. And the reader is a man who is finding some elation, some lift in spirit from the work that is good enough to make him feel that he has found another dimension there of some kind, not a tag to put on his wall, not a sampler piece, but just some sense of the depth and complexity of experience, but an ordered complexity.

[00:27:31.50] Yes. I see. If I understand Mr. Warren correctly, then, there are no simple, easy, guaranteed rules for putting any kind of literary work together, no formula that eases the task for everyone, because writing, all writing, is a process of discovery. The writer is not only discovering the very story he's telling as he tells it, and discovering his characters perhaps at the same time, but he is further engaged in a process of discovering himself, and that there is very little difference finally between the writer and reader, because the reader too is trying to make intelligible a world, a world of experience that has come together in bits and pieces and which may not be intelligible until it's fallen into a form. And it's probably the writer's gift, I suppose, to give the world that intelligible form.

[00:28:28.19] This has been another program of Writers of Today, presenting distinguished authors in a discussion about the writer and his role as thinker and creative artist. Today's guest was American novelist, poet, and teacher Robert Penn Warren. Acting as host and interviewer was Walter Kerr, playwright and drama critic of the New York Herald Tribune.

Distributor: Icarus Films

Length: 30 minutes

Date: 1991

Genre: Interview

Language: English

Color/BW:

Closed Captioning: Available

Interactive Transcript: Available

Existing customers, please log in to view this film.

New to Docuseek? Register to request a quote.