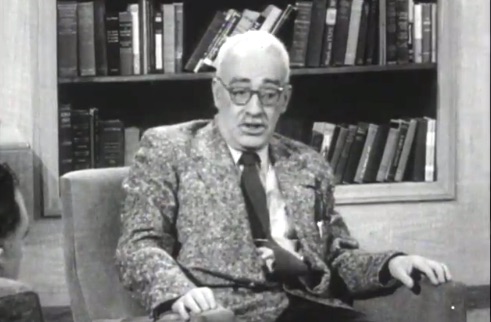

Walter Kerr interviews Frank O'Connor.

Writers of Today: Arthur Miller

- Description

- Reviews

- Citation

- Cataloging

- Transcript

If you are not affiliated with a college or university, and are interested in watching this film, please register as an individual and login to rent this film. Already registered? Login to rent this film.

Each volume of WRITERS OF TODAY is a dialogue between noted literary critic Walter Kerr and one of the best known writers of our time. Produced in the 1950s, these programs provide rare profiles of these men as they discuss contemporary literature and society at the time of their own writing peaks.

Miller expounds his views on the role of theater in society. He contends that the play is 'the last way the human race has to face itself without any intervening machinery,' that movies and television are 'filtering out the intimacy of human contact.' He envisions the playwright as an 'ordinary citizen... who can organize things dramatically.' His criticisms of theater? Prices are too high, the play has taken on the 'aura of a special event,' and audiences are drawn primarily to blockbusters.

Citation

Main credits

Kerr, Walter (interviewer)

Miller, Arthur (interviewee)

Distributor subjects

Drama; Literature; TheaterKeywords

Writers of Today: Arthur Miller

[00:00:08.26] This is National Educational Television, a program produced for the Educational Television and Radio Center.

[00:00:25.14] "Writers of Today," one of a series of programs about the role of a writer as thinker and creative artist. Today's guest is the distinguished American playwright Arthur Miller. Joining in the discussion and appearing as interviewer in this series is Walter Kerr, playwright and drama critic of the New York Herald Tribune.

[00:00:52.37] All right. This is Mr. Arthur Miller, who is, of course, one of the most distinguished playwrights now working in the American theater. When I say the American theater, however, I'm talking about an institution that is shrinking and has been shrinking pretty steadily for perhaps some 20 or 25 years. Every year we've lost a certain number of playhouses to the theater. We've lost a certain number of productions. Getting out of the boards at all, we've lost actors and lost directors. And although Mr. Miller himself has done extremely well during this period and probably doesn't feel the theater is shrinking for him, nevertheless the broad boundaries, the outlines have been undergoing a process of constriction. And I'd like to ask Mr. Miller what he thinks is wrong with the contemporary theater.

[00:01:37.32] Well, as far as the shrinkage of the theater is concerned, I think that the obvious answer which must be mentioned-- although it isn't the whole story-- is the price of tickets. I think if you're going to charge $5, $6, $7, $8 for a ticket you're going to automatically bar a large number of people from the theater.

[00:02:02.46] Of course, even when you say $8, you haven't told the whole story. With the flight to the suburbs and people having to come in for dinner and get baby sitters and so forth, you've run that bill up maybe to $20 or $25, I suppose.

[00:02:13.94] Well, it's an expensive thing. And unfortunately, it has an aura about it now which is that of a luxury which one does on special occasions, perhaps. And it's like expensive jewelry. And of course, under such circumstances the theater traditionally has always died.

[00:02:41.28] Well, this is almost the worst thing that could happen. It could have a specialist kind of audience.

[00:02:45.44] Sure. We're playing now to a sect of a sect of a sect. It's a section of a middle class which is extremely specialized.

[00:02:53.92] Well, I think it accounts too for our smash hit, psychology. In other words, since they're only going to go on very rare, special occasions, then they insist upon gold-letter jobs, and they all converge on the same five or six shows per year with the result that there might be 20 good shows, good shows, ordinarily good shows running in Broadway during the season that always have empty seats.

[00:03:17.30] That's right. I don't want to dwell too long on the economics. But inevitably I think when you're charging that kind of money people lose the relaxation that one must have when one enters a theater. When you've laid down the price of a pair of shoes to get in, you insist on a kind of nervous shock effect, perhaps, which is unfair both to yourself and to the theater.

[00:03:44.91] You mean it's pretty hard for the playwright to be worth $20--

[00:03:47.63] Well, I don't know many playwrights who are worth $20.

[00:03:51.26] I think there are quite a few of them. But you did say before that you didn't think this was the whole answer. I know and I don't myself. Every time I ask somebody why they don't go to the theater, they say it's because it costs too much. While I don't doubt their sincerity, I do doubt whether they understand the whole truth themselves.

[00:04:08.42] I don't think it is the whole answer. It is an enormously important factor at this moment. But I think that the idea of the theater has to be cultivated. I don't think people understand, in general, the difference between living theater in terms of what it ought to be and what it sometimes is and the movies and television. I think that the idea of the theater as being a kind of a place where one celebrates an anniversary or a wedding or something like that, it's robbing the people of a great joy.

[00:04:50.53] Certainly we have lost the drop-in trade, the casual theater-goer.

[00:04:53.45] Sure. Well, nobody can drop in at $8 a drop.

[00:04:55.90] Well, but as a matter of fact now, you see, as I started to say a minute ago, there might be 20 shows operating in New York at a given time that do have seats available, but you can't get people into those shows.

[00:05:05.91] Well, the psychology is perfectly true. I know in my plays that the balcony is the last seat to be sold. And that's a very frightful fact.

[00:05:16.44] A good many people in recent years have found that the $1.50 or $1.65 seats are the hardest to get rid of.

[00:05:22.62] Yes. And I know the case that you might know, a show that raised the price of the balcony and started selling tickets.

[00:05:30.08] Yeah. In other words, the economic problem is not, then, the whole answer. It maybe even perhaps be a result of certain other factors, although it exists.

[00:05:37.05] The fact is, I think, that we've lost the masses in the theater for a long time now. And part of the reason that we've lost them, I suspect, is that our plays are addressed-- it's difficult to say what is a cause and what is an effect. But the way it is now, so many of our plays are addressed to a specialized psychology. They are not attempting to face the real challenge of the theater, which is to say, at least in my opinion, that a playwright ought to be simply another citizen who has one special ability, and that is he feels what everyone else feels, he senses what everyone else senses, but he has the peculiar talent to organize his experience dramatically. It isn't, in other words, the usual idea of a playwright who is some distant figure who sits alone all the time and dreams in the clouds.

[00:06:45.58] There's been some danger of that becoming true of some of our playwrights, though, don't you think?

[00:06:49.55] I think it is a danger. I think that we have gotten an idea in part in the theater that a play ought to not be an entertainment, that it ought not be too comprehensible, that it ought be so complicated that only the most developed and most sophisticated can understand it. I reject that idea principally because I'm not competent really to enjoy anything that is too rarefied. I think that the big job is not to make simple things complicated but to make complicated things comprehensible.

[00:07:30.94] Yes. And so often today there is almost no complexity, let us say, in some of our literary-type plays. By literary-type, I do mean the kind that sound as thought they had come out of a quarterly magazine, have very, very fragile storylines. They may have a certain perception, a certain truth, a certain honesty of characterization but on a terribly fragile, terribly small level. Do you think that's true?

[00:07:51.39] I think it's true. I think that the big challenge is to look at the most unlettered section of the audience to say that they're just as we are, excepting perhaps that they can't speak as fluently or they can't write as fluently and they haven't read as much. I believe that human experience transcends most classes of people and that if one is a real playwright one can find those themes and those ways of saying themes which will hold the attention and the interest of almost every type.

[00:08:27.25] In other words, it's not a matter of a single IQ level. It's not a matter of a college education.

[00:08:32.13] I think if that happens, what we're going to get is a more and more constricted, specialized, and inevitably an academic kind of a theater where it is a theater dressed by a very cultivated playwright to a very cultivated audience, which traditionally in history has ended up with a graveyard.

[00:08:51.09] Mm hmm. And do you have any means of your own as a writer of trying to make sure that you are touching the whole audience?

[00:08:59.55] I have no means, excepting that I have a faith that if I am preoccupied with some theme that somehow, mystically, perhaps, or mysteriously, other people are. I think that sometimes I'm wrong. Sometimes it isn't so. But I couldn't proceed otherwise.

[00:09:22.40] In other words, I'm not trying-- I want to make one qualification here. The movies oftentimes objectively go forth to find out what people are interested in. I don't think you can ever find out. Because by the time you find it out, they're no longer interested in that.

[00:09:39.67] Well, you feel, then, that the author, if he's going to write at all, must have an absolute confidence in himself, that is to say in the fact that he's in touch with his public.

[00:09:49.84] I think that that's the case. I think that if you try to follow them, you will always be behind. And if you try consciously to lead them, you'll get too far ahead.

[00:10:03.32] In other words, you're really having any confidence in your audience too, aren't you?

[00:10:05.73] I believe in them.

[00:10:06.43] Yeah.

[00:10:06.79] I think that they're as intelligent as I am, and I just believe that if I thought of it they have been thinking about it. That's all.

[00:10:14.81] I see. In other words, you think you're getting in touch with something that already exist in them, that is to say that if they come into the theater with a certain preknowledge that you can get hold of, they may not know they have it?

[00:10:23.94] That's it. I think that what I am doing, at any rate, and what I think a real playwright has to do is to say to the audience, in effect, this is what you think you're seeing in life every day and then to turn that around and say this is what it really is, but to begin from the concept that we both share originally, the same vision, the same impulses. And I am merely in the position of one who knows how to organize them in a dramatic moment.

[00:11:02.25] Mm hmm. You're having a common experience, then, out of a kind of common knowledge.

[00:11:05.85] That's right.

[00:11:06.11] But you can touch it, you hope.

[00:11:08.07] I hope.

[00:11:08.68] Yeah.

[00:11:08.97] That is the theory upon which I work. I think that one of the difficulties in understanding this comes from the fact that we look back at the old playwrights whose ages are long since dead and we think, as with Ibsen, let's say, that he originated many ideas, that he was a kind of Einstein, let's say, who truly reached out into unknown territory and made a brand new concept or Shaw or even Shakespeare. I don't believe that. I don't think that you can teach anything to people in the theater in the sense that one instructs people in a schoolroom where one shows them a brand new idea. I think they've had to know it first but not know they know it.

[00:11:58.12] Yes. I know I've often run across, for instance, the didactic impression in the field of satire. People will tell you that, well, maybe drama isn't educative in other forms, but in the case of satire it is. Instead, if you'll check through the history of the theater, you almost always find that satire that is ahead of its time, satire that is really meant to be corrective fails very quickly. The audience simply resents it or resists it because they themselves haven't come in knowing that this thing is ridiculous. However, secretly they may know it.

[00:12:27.01] Yes.

[00:12:27.50] So you wouldn't say, then, that the theater is essentially informative.

[00:12:30.73] It isn't essentially-- it's informative in the sense that it's an interpretation of experience that they have already had. And in that sense, it's an educational experience in the sense that I'm utilizing chaotic materials that lie within and reforming them into a knowledgeable whole.

[00:12:50.95] Yes. You're dealing with knowledge, but it's knowledge that they intuitively possessed and have never formulated for themselves.

[00:12:58.17] That's right.

[00:12:58.80] You're hoping to formulate it for them.

[00:13:00.03] In other words, I'm the guy that goes around and says, well, what is really going on here? I am as confused as they are in the beginning. It takes me a year or two, perhaps, to find out what it is I feel.

[00:13:11.28] In other words, there is a kind of rumbling through the whole society that is at least felt by the audience.

[00:13:16.42] That's right.

[00:13:17.01] They're in touch with it, because they're part of that society. You have to be in touch with it as a playwright. These two things come together, and a spark is made in the theater.

[00:13:24.19] That's, I think, what happens under the best circumstance when it really works.

[00:13:28.83] Yes. Uh huh. Well, now you've been talking about entertaining the audience at the same time. Normally when someone says this, oh, you get a great hue and cry, I think, from certain quarters of our society that say you're going to pander to the audience or you're going to stoop to them and give them some kind of sop that will hold them in the theater. What do you think about that?

[00:13:49.74] I don't think you can do it in a serious play and get away with it anymore. I'm glad you can't. The dullest thing to me is a play that's utterly predictable where I know, I sense that the thing is arranged in order to give me a lesson of some sort. That is simply a vulgarization of originally a very valuable way of working, that is to say I believe that if you tell the absolute truth about anything you're going to teach people something. In other words, the idea to me is it is a great thing to be able to say what's happening. Forget about what ought to happen. That is a field in itself. If we could just know. Imagine if we could know what's going on now.

[00:14:37.21] Yes. In other words, you're not with the idealists who are trying to create a kind of perfect universe or urge the audience on to what ought to be. You're mostly concerned with what is at the present time.

[00:14:47.25] That is, I think, the necessity in the theater. I don't see how you're going to engage people's emotions with something that they have not yet felt.

[00:14:57.32] Mm hmm. And you think that so long as you tell the truth that this in itself will prove exciting and entertainment to an audience, will carry them.

[00:15:03.94] And it will also be a great education. Imagine if we knew the truth.

[00:15:09.54] A very lovely thought.

[00:15:11.06] That would be a great thing. And once, sometimes, in a lifetime a playwright can get at it really.

[00:15:16.50] Now how easy is it to do this in, let's say, the Broadway theatre, the Broadway theater which is so commercial. We ourselves have been talking about commerce here. We talked about economics, the price of tickets, so on and so forth. All of these are factors you have to contend with as a playwright. Is there any clash between worrying about these commercial factors in the theater and worrying about how good a play you manage to write?

[00:15:39.05] With me, there isn't. And I'll tell you, I know there is and there always has been as long as I've been around a cliche that you can't really speak in an adult way to these gum-chewers. You see? I don't believe that. I think that's simply a confession of bankruptcy on the part of the playwright, who really hasn't got such a grip on a truth that no man with any common sense can deny it. I think that the failure-- one waxes back on this idea that the audience is beneath deep thought or whatever simply because he hasn't got any deep thought, really, and he can only lard onto a superficial story some easily bought moral of some sort.

[00:16:30.66] Yes. It's a commonplace in the theater, of course, to talk about the audience as having a 12-year-old mind or something of that kind.

[00:16:36.19] Well, I discovered that, in a serious play, that is, I think that people are of different moods and the theater should be of different moods. In other words, a perfectly serious person can go to see a silly play, and he knows it's silly, and he likes to feel silly that night. That's one thing. If you're going to present to him something that's going to make him suffer, I think he's got a perfect right to ask you that it makes sense and that it really hold together and that it be meaningful. Because I myself don't like to go to the theater and see a serious play unless it's very fun. I don't want to suffer unless there's some point to it.

[00:17:11.71] Yes. In other words, you think that the audience is perfectly capable of going anywhere that you're good enough to take it. It's capable of rising to almost any height, so long as you do your work well.

[00:17:21.29] Absolutely.

[00:17:21.62] You would go along with that.

[00:17:22.83] Absolutely. I think it's so. I would qualify that in one respect, and that is simply that since our theater is so narrow now, that is it plays to so few people, there is an objective difficulty in this sense. If you go out with a play to people who've never been to theater at all, you'll sometimes find that what seems to you in New York to be perfectly simple gets to be very sophisticated in some smaller places where they're not accustomed merely to the conventions of the theater. But that is a relatively small risk. I haven't found that in many places.

[00:18:02.55] And also, it's probably due, I suppose, to the virtual disappearance of the road and the unfamiliarity with convention that comes as a result.

[00:18:08.96] That's right.

[00:18:09.64] In other words, getting them reacquainted with the theater wouldn't be too terrible a proposition.

[00:18:13.09] It isn't. No, I think it can happen in a very short time. I have a friend myself who was an educated fellow. And he objects to the theater he says because every time it really gets interesting they pull the curtain down. And it's simply that he's out of tune with the convention.

[00:18:29.44] Yes, I know. The first time that I ever took my kid to see a play, the curtain came down, went up again, and so forth, except he terribly resented lowering the curtain and not changing the scenery. He could grasp the principle of lowering the curtain as long as the scenery was changed. But otherwise, there was no good reason for this whatsoever.

[00:18:44.36] Yeah.

[00:18:45.13] So he was learning a convention, and, I think, in, perhaps, a very sensible way. Well, to go back to this matter of how far the audience can go. there's no real problem of taking this audience which may have come into the theater bent on entertainment right on up into tragedy.

[00:18:59.08] There is none. The problem is to be that good. And as in most professions, most of the playwrights most the time aren't that good, including myself.

[00:19:10.40] Well, now, just supposing that they are that good, and you said that they can take the audience right up to tragedy, provided they have the personal quality, what about something like poetry? We haven't had poetry in the theater really for a long time. Can the playwright get the audience there too?

[00:19:25.24] He can, but it has to be a dramatic poetry. That's a tremendous problem. And I think that the next new form is going to be a verse form. But to put it in as simple a way as I can, it requires that the poetry take on a whole new attitude if it's to be effective. It has to be verse than I call informative verse. It has got to move, and it's going to act. It cannot be a kind of conceit or a self-conscious use of language.

[00:19:55.91] In other words, it can't be sort of the passive lyricism that a poet writes in his study at all. It's got to come up off the floorboards in some way.

[00:20:03.12] The Theater. Is a vulgar mechanism. It is something that only exists when it is approaching living people.

[00:20:10.21] But there's no conflict, really, between this vulgar level and poetry, because--

[00:20:13.70] Not at all.

[00:20:14.07] --poetry can operate on that level.

[00:20:15.43] Absolutely. But it takes a poet.

[00:20:18.85] Yes. Well, after all, we go to musical comedies, and it never occurs to us to be disturbed by the fact that the lyrics are verse, verse of a kind, sometimes of a very good kind.

[00:20:28.65] Sure. As in everything else, you have to take it to a greater height. And to do that, again, you have to be good. And that's the problem.

[00:20:39.84] I'd like to be just practical for a minute. You're talking about how good you have to be. You're talking about how few men who are that good come along at any given time. We've also said the prices are high, that the theater is shrinking, that not too many people are going, just as not too many great men are writing. Well, why have a theater then? Why not simply go to the movies, go to the other entertainment media?

[00:21:02.59] Because the theater has a very special and unique function, I think, and it is this. It is the last way the human race has to face itself man-to-man without any intervening machinery to commune as a social group about things that really affect the fate and the intimate lives of mankind. The rest of the media, the advanced communication media, the movies and the television are filtering out the intimacy of human contact. I know when I try to write a movie, I feel as though I'm out in the streets shouting trying to reach the people through the camera, through the sound machines, through everything. When I write a play, I feel as though I'm talking in my living room to my fellow citizens.

[00:22:01.14] Well, I suppose, though, that someone who wanted to defend, let's say, the movies or the more mechanical forms of entertainment would say to you, isn't there, nevertheless, a kind of separation between you and your audience, since you do write in your living room and they come together later? And furthermore, of course, you've got to still filter your work through, perhaps, a director, in most cases, and through a number of actors, perhaps even through the men who have put up some money for the entertainment.

[00:22:25.72] That's true. But first of all, just from a technical point of view, it is much simpler to produce a play than it is to produce a movie. All I need yet to this day is a typewriter with a good ribbon in it and a table to write on and a producer. It takes two men to start the whole thing going. You can't start a picture without an army of people all around you. And the word, the address that the writer has to make is drowned in that stuff.

[00:22:56.03] I would make one other point about the theater, and that is that I think we are created and we are made and we develop as much in terms of our verbalizations, in terms of our words more so than any other way. The movie is primarily a machine to make images. So much of what we are and so much of what we feel can never be an image.

[00:23:23.07] In other words, the pictorial image of, say, the motion picture is in itself a thinner image than the verbal image that can be made on the stage.

[00:23:30.11] Certainly. Because we include both. The stage love words. The stage lives off words. The movies hate words. And the movies die when there's too much talk, because the image is so enormous. And I think that the stage, as a result, is closer to life, is closer to reality than the movies ever will be, even though they can go out in the street and shoot the passing traffic, which we can't do, et cetera, et cetera.

[00:23:57.39] How are we going to convince an audience now that this is so? Obviously, at the moment they're not convinced.

[00:24:01.31] Well, I think we've got to write better plays, for one thing. But I think it is also a question of the cultivation of the idea that the theater has a higher mission, that it is not simply another means of fleeting entertainment, that it has had for 2,000 or 3,000 years a civilizing impact on men, and that it remains yet, as I said, the tribune where a citizen, such as myself and the other playwrights, may address quite plainly, simply, and over empty air, so to speak, his fellow citizens.

[00:24:43.55] And if we lose that, if we make everything so mechanized, so complicated, so suffocatingly complex in terms of finances, in terms of editors, in terms of producers, et cetera, et cetera, I think that the individual voice is going to be lost. Everything will become standardized, round, spherical, and a zero.

[00:25:07.15] All plastic, you mean.

[00:25:07.97] yes, all plastic.

[00:25:09.16] Yes. My wife has a phrase for our society. Sometimes she says she thinks it's all really compressed into the single notion just add water.

[00:25:16.21] That's right. Just add water.

[00:25:17.34] I think there's something in it myself. Well, still when you start to talk about the theater as a cultivating force and the theater as a force, in a sense, for intellectual salvation, there's some danger that you may scare people away. And yet you say that the theater, the actual experience of theatre, being in a theater, being directly reached by the actors is unique and should be exciting to the audience. Do you think it's exciting enough at the present time? Do you think they're getting the full impact of this at the present time, the possible impact?

[00:25:44.76] No, they're not most of the time. And the reasons why have to do with, I think, at bottom it's that most of our shows have failed to really embrace America, so to speak, and to have confidence in it, instead of taking a very special, small, supercilious at times and other times a hyper-sophisticated point of view toward it.

[00:26:15.53] Yes.

[00:26:15.95] It's an escape, in that sense. It is not an open confrontation with the great issues and the great emotions that are moving through this society.

[00:26:23.87] You mean that the playwright on the average isn't really touching all that is available in the audience for a response--

[00:26:29.48] That's right.

[00:26:29.97] --that there are untapped responses there.

[00:26:32.54] That's right. I think that this is one of the most exciting times to live in, and it should be one of the most exciting times to write in. And instead, the plays seems to be getting smaller and more specialized, as though we were driven into a corner. And I think it will break out from the playwrighting point of view, well, to put it simply, when there's more guts.

[00:26:53.01] Well, I think that's a very good way to put it. I think it's also a good way to describe your own work. I think too that whenever we can put a fresh face on the theater, whenever we can make them look at it as though we're a slightly new commodity, as I think you did, for instance, in Death of a Salesman when the play took on a fluid form and shape. It was unfamiliar. It wasn't the standard living room. I think that immediately the audience came to you and saw a theater that they hadn't imagined before.

[00:27:21.47] Mr. Miller, then, believes that the theater is a unique form that cannot really be dispensed with, because it can't be duplicated in other forms. And he thinks also, if I'm not misinterpreting him, that it's a universal form, one that appeals steadily, constantly to all audiences.

[00:28:02.41] This has been another program of "Writers of Today," presenting distinguished authors in a discussion about the writer and his role as thinker and creative artist. Today's guest was the noted American playwright Arthur Miller. Acting as host and interviewer was Walter Kerr, playwright and drama critic of the New York Herald Tribune.

Distributor: Icarus Films

Length: 30 minutes

Date: 1991

Genre: Interview

Language: English

Color/BW:

Closed Captioning: Available

Interactive Transcript: Available

Existing customers, please log in to view this film.

New to Docuseek? Register to request a quote.