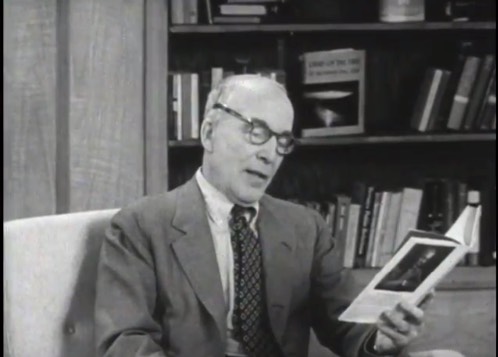

Walter Kerr interviews Archibald MacLeish.

Writers of Today: W. H. Auden

- Description

- Reviews

- Citation

- Cataloging

- Transcript

If you are not affiliated with a college or university, and are interested in watching this film, please register as an individual and login to rent this film. Already registered? Login to rent this film.

Each volume of WRITERS OF TODAY is a dialogue between noted literary critic Walter Kerr and one of the best known writers of our time. Produced in the 1950s, these programs provide rare profiles of these men as they discuss contemporary literature and society at the time of their own writing peaks.

Auden bemoans the declining role of the poet in society. He decries the increasing mechanization of form and yet believes poetry is more personal than ever before. He explains that the problem lies in the grand scale of modern events. How, for instance, might a poem about World War II be written? In defining what makes a poet, Auden says 'If one is stimulated by arbitrary restrictions, that person may be a poet.'

Citation

Main credits

Kerr, Walter (Host)

Bobker, Lee R (Director)

Distributor subjects

No distributor subjects provided.Keywords

Writers of Today: W. H. Auden

[00:00:37.95] This is another in a series of programs called "Writers of Today," a series in which we talk with contemporary writers of distinction about their work and about writing generally. Our guest today is Mr. WH Auden, one of the most distinguished poets of our time and in fact a man who has come very close to giving a name to our time, the Age of Anxiety. In addition to his work as a poet, Mr. Auden has also busied himself as a dramatist, a librettist, and as a very stimulating critic. Suppose we join Mr. Auden.

[00:01:18.89] Mr. Auden, you once contributed to a symposium called Poets at Work, I think.

[00:01:24.76] I believe I did, yes.

[00:01:25.96] And at same time, I understand that you don't really quite regard the writing of poetry as work.

[00:01:31.87] Well, it depends what you mean by work. I think there are very few activities in life that really can or ought to be pure work, that on the one hand, you've got things-- one must eat. One must sleep. One must drink. Those are necessities.

[00:01:48.06] On the other hand, I suppose one could say that one must do one's duty. Anything that comes between that, which is something you don't have to do but you do because you like doing it, I would call play in that sense.

[00:02:00.17] Play is anything that the body doesn't demand and that the moral conscience--

[00:02:05.42] Conscience doesn't demand.

[00:02:06.39] --doesn't demand. I see. And poetry comes within this classification.

[00:02:08.76] Yeah, because people often ask you, you know, well, why do you write poetry? And what answer can I possibly give except I do this for fun. I sometimes quote to people the nice story about Dr. Cushing, the famous brain surgeon, who was once consulted by an intern, a very promising intern, as to whether the intern should take up surgery.

[00:02:36.73] So Cushing said, well, I'll just ask you one question. Do you like the sensation of putting a knife into living flesh? And the intern said, no, I don't think I do. Cushing said, don't become a surgeon. And that applies, I think, to all activities of that sort, of which writing poetry is one.

[00:02:56.13] Yes. Well, suppose now, suppose a writer came to you and said he wanted to be a. poet. What question would you put to him?

[00:03:01.77] I'd first of all, I think, find out whether he really loved language. It's a bad sign if somebody says, oh, I have important things to say. But poetry is one of the things which-- a quotation I think EM Forster comes from, said an old lady says, how can I tell what I think until I see what I say? And a person who starts by being too anxious, I have a message, then I suspect that they are not really talented for poetry.

[00:03:35.04] In other words, there's a certain lack of love there and playful affection--

[00:03:39.85] For the medium, just as Valery said, if a person's imagination is stimulated by arbitrary restrictions, rules, like in a game, then he may be a poet. If his imagination is suppressed by those, then he might be something else. But he isn't a poet.

[00:03:59.82] In other words, you think the restrictions are very good.

[00:04:02.61] Oh, they're the whole fun of it. After all, you couldn't play any kind of game without some kind of rules.

[00:04:07.95] And you think of-- I'm sorry.

[00:04:09.74] Yeah.

[00:04:10.01] You think of them not as codes of law, but game rules.

[00:04:13.55] Yes. They're game-- because you're allowed to choose your rules. But once you've chosen them, you have to obey them. And the enormous fun of poetry to me as compared with prose if that suddenly you're faced with a problem. Now I've got to have a word here, what shall we say, it's three syllables long, with an accent on the second syllable, rhyming with another word, and meaning dry. And all right I have to find-- and suddenly you find that you say something which is true which you hadn't thought of saying and you wouldn't have thought up if it hadn't been for these kind of restrictions.

[00:04:54.49] In other words, the restrictions finally give you a certain freedom of choice. You must make a choice. And that in itself is a freedom.

[00:04:59.54] Yes, like all choice is. You can't choose absence in a void.

[00:05:03.85] And this freedom of choice has something to do with your concept of play?

[00:05:07.06] Yes.

[00:05:07.38] That you are enjoying this freedom within arbitrary limitations.

[00:05:11.26] Yes.

[00:05:11.70] I see. They're not actually I think quite arbitrary, because nobody I think can explain how it is that for a given poem you feel this particular kind of form is right. And there is a right form for it.

[00:05:26.50] You may spend days doing something and get stuck. You cannot get it right. It looks all wrong. You suddenly find, shall we say, oh, these two lines have two be two syllables shorter, and the whole thing comes out.

[00:05:36.99] But the poem has finally taken on its own authority.

[00:05:40.36] Yeah. That's why when people ask you what a poem means that you've written, I always say, well, your guess is as good as mine, because they are the words. They either make sense or they don't.

[00:05:53.31] You've set something in motion.

[00:05:54.74] Yeah.

[00:05:55.06] And perhaps even tyrannically in motion.

[00:05:57.16] And now there it is. And what I think it means has nothing to do with it, what does it mean.

[00:06:04.22] Well, now this concept of poetry as essentially play hasn't always been widely held. Poetry has been supposed to have other functions of a much more perhaps useful kind or dictatorial or helpful kind in society.

[00:06:20.76] Well, I think probably the origins in poetry lie in magic.

[00:06:27.95] In magic?

[00:06:28.53] I think that it was probably originally thought that if you arranged words in a certain way, they could make certain things happen. After all, you get old women, peasants in the country who if they burn their finger will recite a charm like, "there came two angels out of the north. One was fire and one was frost. Out fire and in frost. in the name of the father, the son, and the holy ghost," where presumably originally they thought if you said these words, it would actually have an effect on your finger.

[00:07:00.51] The words constitute a charm.

[00:07:02.62] Though I think very early, as soon as poetry really becomes recognizable as poetry, that completely magical view disappears.

[00:07:15.46] Now, when you use the word magic, I'm assuming that you don't mean to confine it simply to simple folk charms, but to extend it to larger pieces of poetry, perhaps didactic poetry.

[00:07:27.48] You mean, Mr. Kerr, that you're asking whether I disapprove of didactic poetry?

[00:07:33.15] Well, I was trying to avoid bringing up such moral judgments here.

[00:07:36.97] Well, I think it's a very interesting point, actually, because magic after all, what magic tries to do when applied to people is to make them think or act in a certain way without having to choose it so that they don't make a choice. That's what magic tries to do.

[00:07:56.76] You mean, magic tries to impose itself on their wills?

[00:08:01.70] Yes, so that they aren't aware of making a choice. Now, there's obviously no reason why didactic poetry shouldn't exist where there's no doubt about the truth. For example, supposing in order to remember it, one says 30 days hath September, April, June, and November.

[00:08:27.11] Or it wouldn't matter in a thing where it's a matter really of indifference what you buy. Supposing one would have a rhyme advertising a certain kind of toilet soap. Well, I assume that the law protects me against a soap that is actually poisonous or that leaves me dirtier than I was before. Well, therefore, if they can persuade me to buy one sort than another doesn't matter.

[00:08:50.60] You see no harm in that.

[00:08:51.60] No. But in every matter where choice is really important for the person to choose something, even if it's important they choose the right thing, then I think magic is deplorable.

[00:09:04.36] In other words, you don't really approve of the effort to persuade in this strong, strong way.

[00:09:09.64] No, I mean, because the medium really won't do it. And I think it's immoral to.

[00:09:15.99] Well, what about the relationship of artifice and sincerity in life.

[00:09:22.67] Well, sincerity it always seems to me is something rather like sleep. I mean, if you try to get it too hard, you won't. It'll just defeat yourself if you try to be too sincere, just as if you try to go to sleep you won't.

[00:09:37.29] Now just as people have bouts of sleeplessness, sometimes people have bouts of insincerity. Well, when you can't sleep, maybe you want to change one's diet. When one finds that what one is writing doesn't seem to be genuine, perhaps one ought to change one's company.

[00:09:54.58] Oh. I know that you once spoke as though animals and angels could be sincere, but that humans had to be actors first before they could become the thing they were acting.

[00:10:10.96] Yeah, because they're changing all the time. An animal remains what it is through its life. It doesn't have a history, apart from just a biological history. It doesn't have a real history so that it can't be anything but sincere in one sense.

[00:10:26.65] It can't help itself.

[00:10:27.84] Yeah. But therefore one couldn't really apply the word. But a human being who is always having to become something else from what he is now has to practice a bit to get there so that you cannot live without a certain amount of acting, which is fine, because other people can see it too.

[00:10:52.52] Yes. In other words, it's all right to adopt an artifice if in adopting the artifice you hope to produce in yourself the actual quality.

[00:10:59.99] Yes.

[00:11:00.29] We're doing it all the time as matter of fact.

[00:11:02.02] Yeah.

[00:11:02.49] And it's not entirely irrelevant to the poet's problem, is it?

[00:11:05.53] No. No, not at all.

[00:11:07.18] As a matter of fact, I think you wrote a poem that may have something to say about this.

[00:11:12.32] Well, I think I know the one you're referring to. Of course, it's very one-sided, because it is deliberately a polemical poem, which the title came from Shakespeare's As You Like It, where a character says the truest poetry is the most feigning.

[00:11:27.98] The truest poetry is the most--

[00:11:29.67] The most feigning.

[00:11:30.62] I see.

[00:11:31.09] You see.

[00:11:32.04] Do you remember the poem?

[00:11:34.08] I think so. "By all means, sing of love. But if you do, please make a real old proper hullabaloo. When ladies ask, how much do you love me, the Christian answer is, cosi-cosi. But poets are not celibate divines. Had Dante said so, who would read his lines?

[00:11:57.91] Be subtle, various, ornamental, clever. And do not listen to those critics ever whose cruel provincial gullets crave in books plain cooking made still plainer by plain cooks, as those the muse preferred her halfwit songs. Good poets have a weakness for bad puns.

[00:12:18.90] Suppose you're Beatrice be, as usual, late and you would tell us how it feels to wait. You're free to think what may be even true. You're so in love that one hour seems like two.

[00:12:30.85] But write, 'as I sat listening for her call, each second longer, darker seemed than all'-- something like this but more elaborate still-- 'those raining centuries it took to fill that quarry whence Endymion's love was torn.' From such ingenious fibs are poems born.

[00:12:50.73] Then, should she leave you for some other guy or ruin you with debts or go and die, no metaphor, remember, can express a real historical unhappiness. Your tears have value if they make us gay. 'Oh happy grief' is all sad verse can say.

[00:13:10.46] The living girl's your business. And some odd sorts have been an inspiration to men's thoughts. Yours may be old enough to be your mother or have one leg that's shorter than the other or play lacrosse or do the modern dance. To you, that's destiny. To us, it's chance.

[00:13:28.85] We cannot love your love 'til she take on through you the wonders of a paragon. Sing her triumphant passage to our land, the sun her footstool, the moon in the right hand, and seven planets blazing in her hair, queen of the night and empress of the air. Tell how her fleet by 19 swans is led, wild geese write magic letters overhead, and hippocampi follow in her wake, with Amphisboene gentle for her sake. Sing her descent on the exultant shore to bless the vines and put an end to war.

[00:14:05.87] If halfway through such praises of your dear riot and shooting fill the street with fear and overnight as in some terror dream poets are suspect with a new regime, stay at your desk and hold your panic in. What you are writing may still save your skin. Re-sex the pronouns. Add a few details. And lo, a panegyric ode which hails-- how is the Censor, bless his heart, to know-- the new pot-bellied generalissimo.

[00:14:37.67] Some epithets, of course, like "lily-breasted," need modifying to say "lion-chested," a title, "goddess of wry-necks and wrens," to "great Reticulator of the fens." Bu in an hour, your poem qualifies for a state pension or his annual prize. And you will die in bed, which he will not. That silly sausage will be hanged or shot.

[00:15:01.38] Though honest Iagos true to form will write "shame" in your margins, "toady," "hypocrite," true hearts will hear the notes of glory and put inverted commas round the story, thinking, "old Sly-Boots, we shall never know her name or nature. Well, it's better so."

[00:15:21.85] For given man, by birth, by education, Imago Dei who forgot his station, the self-made creature who himself unmakes, the only creature ever made who fakes, with no more nature in his loving smile than in his theories of a natural style, what but tall tales, the luck of verbal playing, can trick his lying nature into saying that love or truth in any serious sense, like orthodoxy, is a reticence?"

[00:15:53.83] Gosh. As I said, this mustn't be taken to too seriously. This poem is deliberately one-sided.

[00:15:59.17] Don't sell it down the river. I'm convinced. I wonder. I wonder, does this general notion of poetry as play and also the idea of truth coming from and through feigning, does that in any way explain in part the relative estrangement of the poet in our society?

[00:16:20.68] There are, I think, particular problems maybe about poetry as a medium which makes it difficult for people. In living in this particular technological age, it's an age-- poetry is is a kind of ritual. And it also is rhythmical. It has repetitions.

[00:16:41.29] Now I think repetition in people's minds now is so associated with the dullest parts of life, of routine, punching a time clock, and so on, or road drills, that they don't see that anything that repeats, as poetry with the rhythm, is to them a little antipathetic.

[00:17:01.26] Has this mechanization that you're talking about in any way depersonalized matters so that the poet's function is no longer so personal?

[00:17:11.42] Well, in one sense, I think one could put it the other way, that the difficulty for a poet living in a technological age is that in fact he can only write about personal matters. When one things in the past how much poetry there was written about public events, and now it's almost impossible to do. Questions interest me very much why [INAUDIBLE].

[00:17:38.18] But I think the reason is that in order to write about, say, to celebrate a hero or a heroine, [INAUDIBLE], they must combine a virtue or excellence of some kind with power. Now, in a technological age, power is taken over by the machine. And however excellent the person may be, the power isn't theirs. It's in the machine.

[00:18:06.71] I mean, all right, supposing you think of Saint George and the dragon. Saint George plunges the spear into the dragon. Well, it is really his act. Supposing Saint George now gets into an airplane and drops a bomb from 20,000 feet on the dragon. Although his intention is the same, the result is the same, his act really is pressing a button. It's not his personal act. And that makes an enormous amount of life simply not available, I think, to poetry.

[00:18:36.72] I no longer seems a heroic--

[00:18:38.28] Because you no longer have this personal relation to it. For example, Yeats was able to write great poetry about the Irish civil war. First of all, it was on a very small scale.

[00:18:51.86] The participants were his personal friends. It took place in places in Dublin which he'd known from childhood. So writing is personally related to that. If somebody would try to write about the Second World War, it's on too vast a scale. There's really nothing you can do with it.

[00:19:08.94] It's difficult for the individual man to see himself as heroic in it?

[00:19:13.16] Well, he can only see his part. He can't really make sense of the whole thing.

[00:19:17.70] I see.

[00:19:18.76] But I think the only thing that will do for a thing like a modern war is straight reporting, factual reporting, candid camera, statistics, and so on. The only person who could write a poem would be God.

[00:19:33.27] Well, there is also, it seems to me, I think from what I've read of your work to that it seems to you, a pressure on the poet nowadays, a pressure that comes from the fact that he can't see a future, not "the future" but "a future" at the present time. Does that bother him?

[00:19:50.88] Yes. I think one of the difficulties for any artist now in any art is that it's not a question of one's own personal insecurity, which often can be a great stimulus. After all, the thought of death has often produced wonderful poetry. But in the past, people had a reasonable feeling when they were writing the kind of world that would exist 50 or 100 years after them would be more or less the same world.

[00:20:20.77] Now we have no guarantee that it will be. In fact, we're pretty sure it won't. And that makes it, I think, very difficult to resist the kind of pressure to have an immediate success, you know, to improvise and all those kinds of pressures that are on us.

[00:20:34.48] You mean poets no longer think of themselves as being in a continuing tradition.

[00:20:40.13] Well, it needs an awful work to think about it. In one sense, we're also in a different position with regard to tradition than the past was, because in the past tradition and keeping tradition meant you made a very slight alteration in the immediate tradition of the past. Now every poet has the whole of the past available to them. And he has to pick and choose from this.

[00:21:08.82] He has primitive forms.

[00:21:10.02] Yes. Old [INAUDIBLE] culture, I mean, absolutely everything, in a technological civilization, one knows. It's not good pretending one's naive about it, come on, is it?

[00:21:18.58] No.

[00:21:18.96] And the pressure, therefore, [INAUDIBLE] becomes all the stronger.

[00:21:24.31] Well, now you've mentioned three or four different problems besetting the contemporary poet. How does the poet manage, considering the problems he's faced with? How does he live nowadays?

[00:21:35.31] Well, how does he live? I don-'t-- that depends, obviously. I doubt very few poets indeed, I think, are able to make a living directly out of doing nothing but poetry. Of course, you get jobs of various kinds through it. But it has certain advantages, that you know when you start you're not going to live by it, so you make your arrangements accordingly.

[00:21:59.34] Most of them I imagine go into teaching.

[00:22:01.40] A lot of them do, yes. It has advantages and disadvantages. There's been a lot of talk and discussion about the role of colleges as patrons of the arts. And I must say, I think they've done a wonderful job in this.

[00:22:18.43] It can be dangerous. When it is, I think it's largely the poet's fault. Ideally, of course, he should be asked to do nothing but write an epithalamium for a manager or faculty meeting or a manager or faculty member or what should we say, yes, an elegy on the death of a trustee. But presumably, we cannot see that utopia.

[00:22:45.07] The danger, I think, is that when a poet takes a job in a college and either talks about his contemporaries or tries to teach "creative" in quotes writing, because that I think is much too near what he's doing and is apt to make him much too self-conscious.

[00:23:06.95] I see. You mean he's engaged in cerebration, in formalized thinking.

[00:23:12.61] And then it comes to the point of saying, well, this is the right way of writing, you know? There's a certain kind of conformance that's bound almost to come in. And it's awfully important that writers aren't afraid to write badly. You must hope that you don't. But the moment you are really afraid of writing badly-- I must never do it-- then you will never write anything any good.

[00:23:33.08] I see. Well, a poet mustn't be listening then to his own classroom strictures as he is at work.

[00:23:37.84] No.

[00:23:38.29] He must be a little freer than that. Apart from the immediate poetic problems, the problems that are entirely peculiar to our own age, is there any larger problem that remains to be solved at the present time for the poet?

[00:23:52.62] Well, there's the problem which is in one sense insoluble which affects the whole of poetry really written in the last, what should I say, nearly 2,000 years, that's in the post-Classical period, which is what I would call development of a sense of history. That is to say that life, a person becomes something. When Keats quite rightly makes the Grecian ode say, "beauty is truth, truth, beauty", for the Greek's it was. Neither for Keats or for us is that the case. There's a distinction between these things. And there's a problem always of reconciling poetry which by nature deals with being with trying to represent becoming.

[00:24:45.23] I see. You're saying now that the Greek poetry or classical poetry generally was concerned primarily with representing being.

[00:24:53.03] Yeah. That's how they thought, that a person was something which didn't change. If you were a hero, you're a hero.

[00:25:00.86] I see.

[00:25:01.62] If you're a churl, you're a churl. And you can't change from one thing into another.

[00:25:06.24] If you're a tragic hero, you're pinned to a set of circumstances.

[00:25:09.49] Yeah, so that the tragedy, in Greek-- the Greek tragedy is always really a tragedy of situation rather than a tragedy of temptation. If you take the difference between say Oedipus and Macbeth, where there's nothing that Oedipus can do once the play starts. Everything's been done.

[00:25:33.16] Except find out what has--

[00:25:34.17] There's not point at which you can say, really, he should have done something else [INAUDIBLE]. At every step, you watch Macbeth, you can sort of say, now don't that. Do that.

[00:25:45.02] I see. So Macbeth is becoming what he is at the end of the play.

[00:25:47.47] Yes. I mean, at the beginning he was a brave warrior. At the end he's the sort of fear-crazed, guilt-ridden creature of the "tomorrow, tomorrow, tomorrow."

[00:25:54.45] And you think this is the result of the development of the historical sense, of the awareness of becoming?

[00:25:58.87] Yes. Of a personal history, yes, which means artistically it's very difficult, because becoming can only be represented in a series of stages. And it's arbitrary how many you show, while real becoming, as we know, is a continuous thing.

[00:26:15.89] But I think about that. It just makes it more interesting, maybe, to be a poet, but more difficult.

[00:26:22.16] More difficult to represent becoming?

[00:26:23.96] Yeah. But on the whole I don't know if I had to-- the best definition of a poet I know I think is Thoreau's. He said a poet is somebody who having nothing to do finds something to do. And the best description I think I know of the artistic process is a wonderful passage in Virginia Woolf in The Waves.

[00:26:47.65] "There is a square. There is an oblong. The players take the square and place it upon the oblong. They place it very accurately.

[00:26:56.58] They make a perfect dwelling place. Very little is left outside. What was inchoate is now stated. We are not so various or so mean.

[00:27:06.91] We have taken oblongs and placed them upon squares. This is our triumph. This is our consolation." I think it's the best description of art ever heard.

[00:27:17.05] We've been talking with the distinguished poet WH Auden, who has been telling us among other things that for him, the writing of poetry is an act of play, play in perhaps a very special sense, but play in the sense of being a freedom of choice on the part of the poet. He's doing something that he doesn't have to do out of conscience or out of simple physical necessity.

[00:27:42.30] And this has all kinds of ramifications for the practicing poet who is going to work. It has all kinds of ramifications for the reader. We've talked about some of the problems of our time, some of the problems over the whole span of history. And I think that Mr. Auden has been extremely stimulating on all of them.

Distributor: Icarus Films

Length: 30 minutes

Date: 1991

Genre: Interview

Language: English

Color/BW:

Closed Captioning: Available

Interactive Transcript: Available

Existing customers, please log in to view this film.

New to Docuseek? Register to request a quote.