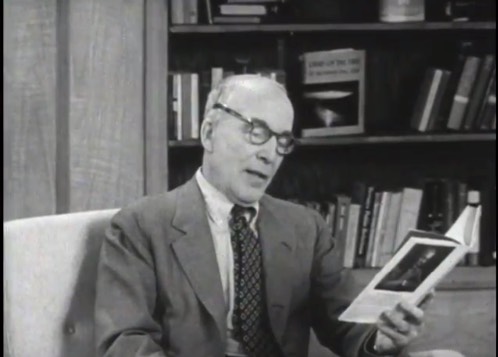

Walter Kerr interviews Arthur Miller.

Writers of Today: Archibald MacLeish

- Description

- Reviews

- Citation

- Cataloging

- Transcript

If you are not affiliated with a college or university, and are interested in watching this film, please register as an individual and login to rent this film. Already registered? Login to rent this film.

Each volume of WRITERS OF TODAY is a dialogue between noted literary critic Walter Kerr and one of the best known writers of our time. Produced in the 1950s, these programs provide rare profiles of these men as they discuss contemporary literature and society at the time of their own writing peaks.

Librarian of Congress, FDR Cabinet Member, and Pulitzer Prize Winner, MacLeish shares his concerns about abstract poetry. 'An abstraction remains an abstraction - you don't know anything but that formula.' Of his drive to write poems, he states simply 'Man I am, Poet must be.'

Citation

Main credits

Kerr, Walter (Host)

Bobker, Lee R (Director)

Distributor subjects

No distributor subjects provided.Keywords

Writers of Today: Archibald MacLeish

[00:00:35.00] I'm Walter Kerr, and this is another in a series of programs called "Writers of Today." Our guest today is Mr. Archibald MacLeish, who is not only one of the best-known poets of our generation, a man who has won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, but who, because he has also been Librarian of Congress and has held responsible positions in the government, qualifies too as a man of action. Suppose we join Mr. MacLeish.

[00:01:06.18] Mr. MacLeish, I have a question I'd like to ask you. I warn you, it's from one of your own most recent poems.

[00:01:12.91] I'm warned.

[00:01:14.49] "Why do we labor at the poem age after age, even an age like this one, when the living rock no longer lives and the cut stone parishes? Holderlin's question. Why be poet now when the meanings do not mean, when the stone shape is shaped stone? Durftiger Zeit, time without inwardness? Why lie upon our beds at night holding a mouthful of words, exhausted most by the absence of the adversary? Why be poet?"

[00:01:50.59] Well, it's a fair question. I think the answer's there, if you let me have the book. I don't carry the words around in my mind.

[00:01:58.34] "Why be poet? Why be man? Far out in the outermost Andes, mortised enormous stones are piled. What is man who founds a poem in the rubble of wild world wilderness. The Acropolis of eternity that crumbles time and again is mine, my task. The heart's necessity compels me. Man I am. Poet must be. And the labor of order has no rest to impose on the confused, fortuitous flowing away of the world form, still cool, clean, obdurate, lasting forever, or at least lasting, a precarious monument promising immortality, for the wing moves and in the moving balances.

[00:02:52.55] Why do we labor at the poem? Out of the turbulence of the sea, flower by brittle flower, rises the coral reefs that calms the water. Generations of the dying fix the seas, dissolving salts in stones. Still trees, their branches immovable, meaning the movement of the sea."

[00:03:19.03] I suppose the coral insect has very little choice as what he's going to do about the destiny that throws him into the salt wave. And yet these forests of stone he creates do still the water and mean the movement of the sea. I don't know. It is a fair question, I suppose, even if I did ask it of myself.

[00:03:45.40] Why in a time in which, as somebody said, matter doesn't mean and meaning doesn't matter, why concern oneself with an art which has for its end meaning? And the answer I would give myself is that one, that what one is constantly attempting to do is to catch and hold the flowing away of the world, the flowing away of one's inward emotional life, hold it so that one can not only see it but feel it, feel it. Jung says in-- this is too long an answer to this question--

[00:04:27.27] Oh, I'm very interesting.

[00:04:28.23] Let me put one more phrase to it. Jung says in the "Answer to Job," which has just been published in England, that existence is only real when somebody is conscious of it. And I would suppose that this is one of the great difficulties in our time, that existence isn't particularly real. And therefore now, if ever, there's a need for the labor by which one does become conscious of existence, which is the labor of art. Does this make any sense?

[00:05:00.41] Yes, indeed. I'd like to ask a further question. When you talk about the building of form or you talk about the slow accumulation of the coral reef, you don't just mean that poetry is the struggle to create order. You mean that it's the struggle also to freeze it where it can be seen or where we become conscious of it?

[00:05:19.38] Not so much freeze it, I would say, as compose it. The running by of experience doesn't of itself have form, it would seem to me. One becomes aware of form only in those actions of selection, which are really the actions of art. What troubles me about this durftiger Zeit, this time without inwardness, Holderlin's question, what troubles me about it is not so much that it is without inwardness as that it seems to me to be truly without meaning. We live our lives with abstractions. We are occupied wholly with abstractions.

[00:05:59.45] You find a man like Bertrand Russell saying that whatever can be known can be known by science, which means that whatever can be known can be known in abstractions. And yet an abstraction remains an abstraction. You don't know anything but that formula.

[00:06:13.92] But we know that, even, for instance, in the universities. I remember how astonished I was when I gradually or finally realized that the liberal arts had really become the scientific liberal arts--

[00:06:24.01] Yes.

[00:06:24.95] --that instead of dealing mostly with the appreciation of the arts or with taste for the arts or what the arts were in themselves, they had become really scientific investigations into proofs about the arts.

[00:06:36.05] Exactly. And therefore a series of abstractions about the arts. This is why I occupy myself now and completely occupy myself most the time while school keeps trying to teach at Harvard and teaching, in part, a course having to do with poetry. And the importance of this, to me, not of my course, but the importance of the subject seems to me to relate to what we're talking about. You don't get a sense of reality. You don't get the hunger for reality unless somehow or other you bring yourself face to face with what seems real. And the abstraction never seems real.

[00:07:13.59] Of course, education can't help having a large body of abstraction in it. There's no way to teach a great many things without reducing these things to abstraction.

[00:07:23.36] Yes. But what troubles me about this age, if it is an age, is not so much that as it is a kind of-- is it too much to call it spiritual impotence?-- which seems to me to result from the overwhelming of oneself with abstract notions, with tools, instruments, means, and so forth. Well, of course, this perhaps comes ill from me, because to me a poem also is a tool or instrument. Only it is a tool or instrument which has as its use the approach to reality, the reality of experience, that is, in Jung's phrase, the consciousness of experience.

[00:08:07.60] Yes. But you are talking about a poem as a tool or an instrument.

[00:08:12.54] I think I am, yes.

[00:08:13.52] What, if I may ask, about a very famous poem of yours, the "Ars Poetica," which you wrote a long time ago and which has been reprinted in practically every anthology ever published.

[00:08:23.51] I know. I know.

[00:08:24.51] It doesn't seem quite to fit, off-hand.

[00:08:26.49] I keep hearing about it.

[00:08:27.75] You do?

[00:08:30.01] Well, perhaps the best thing to do would be to read it. I can defend it, but I know very well why you want me to. "Ars Poetica." "A poem should be palpable and mute as a globed fruit, dumb as old medallions to the thumb, silent as the sleeve-worn stone of casement ledges where the moss has grown. A poem should be wordless as the flight of birds. A poem should be motionless in time as the moon climbs, leaving, as the moon releases twig by twig the night-entangled trees, leaving, as the moon behind the winter leaves, memory by memory the mind.

[00:09:17.11] A poem should be motionless in time as the moon climbs. A poem should be equal to. Not true. For all the history of grief an empty doorway and a maple leaf. For love the leaning grasses and two lights above the sea. A poem should not mean but be."

[00:09:43.51] Well, of course, you aren't asking the question that most people ask me about this, which is whether this isn't-- they don't ask me. They tell me. This is an assertion that a poem has no interest in meaning, has nothing to do with meaning. It simply exists in itself. This is not what you're suggesting. Because clearly what I think this poem says, at least I think it says it, is that a poem's meaningfulness comes not from argumentation or logic. It comes from the existence of the thing itself, the weight of the object of art. But I take it that your interest in this poem is--

[00:10:18.30] It does lead me to the impression that the poem is-- you talk about medallions felt to the touch.

[00:10:23.39] Yes.

[00:10:24.10] You talk about globed fruit. Now it does lead me to the impression that the poem is an object--

[00:10:29.49] Yes.

[00:10:30.08] --an object that is more or less still in time--

[00:10:32.85] Yes.

[00:10:33.53] --that does not move by itself.

[00:10:35.47] Which I do not believe.

[00:10:36.48] Which you do not believe. I see.

[00:10:37.79] This is, of course, where I must enter the confessional, at least so far as that poem goes. I will stand on that poem up to the point at which you've caught me, the point at which it seems to say that a poem is an object. Whereas to me a poem seems to be an action.

[00:10:59.09] Now this is a further development in your own thinking about your own work.

[00:11:04.51] Perhaps a further development, or perhaps simply a more correct understanding of what I have felt in the past. I don't know.

[00:11:10.00] I see. In other words, you think it was there all the time but needing for the statement.

[00:11:14.86] Well, certainly what happened to me-- that poem was written in the '20s. And what happened to me, like what happened to almost everybody else who lived through the '30s, it rather modified one's sense of the background. I found myself-- again, can I go to a text?

[00:11:32.45] I wish you would.

[00:11:33.00] I found myself writing this sort of thing, a series of poems called "Frescoes for Mr. Rockefeller's City," called so because Rockefeller Center was in process of construction at the time. And as you perhaps may recall, Diego Rivera was asked to paint a great fresco for the entrance hall.

[00:11:56.18] And there was a great fuss about--

[00:11:57.42] And there was a great fuss about it, and it came down. And it seemed to me that perhaps one could write a series of poems that wouldn't come off the wall so easily. So hence frescoes. And this is one, "Burying Ground by the Ties." Railroad ties. Ayee. Ai. This is heavy earth on our shoulders. There were none of us born to be buried in this earth. Niggers we were, Portuguese, Magyars, Polacks. We were born to another look of the sky, certainly.

[00:12:31.84] Now we lie here in the river pastures. We lie in the mowings under the thick turf. We hear earth and the all-day rasp of the grasshoppers. It was we laid the steel to this land from ocean to ocean. It was we, if you know, put the UP through the passes, bringing her down into Laramie full load, 18 mile on the granite anticlinal, 43 foot to the mile, and the grade holding.

[00:12:58.19] It was we did it, hunkies of our kind. It was we dug the caved-in holes for the cold water. It was we built the gully spurs and the freight sidings. Who would do it but we and the Irishmen bossing us? It was all foreign-born men that were in this country. It was Scotsmen, Englishmen, Chinese, Squareheads, Austrians.

[00:13:21.60] Ayee, but there's weight to the earth under it. Not for this did we come out to be lying here nameless under the ties and the clay cuts. There's nothing good in the world but the rich will buy it. Everything sticks to the grease of a gold note, even a continent, even a new sky.

[00:13:45.46] Do not pity as much for the strange grass over us. We laid the steel to the stone stock of these mountains. The place of our graves is marked by the telegraph poles. It was not to lie in the bottoms we came out and the trains going over us here in the dry hollows."

[00:14:11.34] Well, you come back to your own country, and I suppose that in itself is a kind of discovery. And you come back to it in a time in which all the seamings have changed. Nothing that you took for granted can be taken for granted any longer. And you certainly opened to yourself long perspectives back into the history of that country, which were very different from the perspectives you thought you saw. You see this sort of thing, the people who built the UP, the Chinese who came from the West Coast up and the Irish who carried her through from the ease, the thousands of men buried along those rights of way.

[00:14:50.52] You're moved by it, and you write a poem. And the question is, is it a poem? That's, I suppose, a perfectly fair question. Is it? And is it mere communication, a mere attempt to persuade? Or does it have the quality of existing within itself? And this carries me back to that "Ars Poetica" line.

[00:15:15.53] Well, certainly there is an enormous contrast now between these two poems--

[00:15:19.39] Yes.

[00:15:19.79] --as you say, and a very obvious one. And the one does suggest-- and I don't think you meant it to, but it suggests, I suppose, to many people the ivory tower, and the room in the garret, the man alone with his wonderful little artifact, the thing that he has wrought. And the other one is, of course, all participation. It almost sprawls with the going surfaces of things.

[00:15:44.50] Yes. And more than participation, because I suppose there is a barely concealed desire in this poem, "Burying Ground By the Ties," that the poem should have consequences, that the reality of the experience, which this poem might perhaps under fortunate circumstances communicate, might have consequences in people's feeling and people's feeling about the country and people's feeling about each other. That desire, I think, is in it. I think it comes out. At least> It seems to me to be there.

[00:16:22.51] You hope now that this poem will act on people in the way that the earlier poem did not?

[00:16:27.56] Hoped, certainly. There's no question about that. Whether I hope so now is something that I puzzled about a good deal. That is to say it seems to me there is obviously a risk in carrying the use of poetry to move, to persuade, to have consequences by way of persuasion. There's a risk in carrying it too far. It can be carried too far. You can get, after all, poetry which is nothing but propaganda, which destroys itself. It becomes an argument, an argument with the world and an argument which you can lose. You lose it at the very start. And then again, there's, well, not only the possibility but the very great probability that poetry which commits itself too definitely in this way will perish with the time out of which it comes. So one talks about the poets of the '30s, you know, a number of whom ceased to write after the '30s and whose work seems to have receded to the background.

[00:17:36.65] Well, in the '30s, as I remember them, our commitment, our literary commitment to the going concerns of the day and to all of the immediate social issues was very great.

[00:17:46.15] Very great.

[00:17:46.65] In fact, it was pretty much insisted upon.

[00:17:48.30] Yes. Well, surely the Marxist critics did their best to drive that home. And the rest of us, I think, to some extent, but for different reasons, accepted it. And yet, this is not solely an American phenomenon or a phenomenon of my generation.

[00:18:08.63] Yeats toward the end of his life asks himself in a poem whether that play of mine sent some men out whom the British shot. Well, his play had sent men out, and they had been shot. And he had to make his peace with that. The problem for him, I think, was not so much whether his poetry had had consequences which were disastrous or unhappy. The problem for him, as for almost anybody else thinking about it seriously, was whether and in how far his poems lost or gained by that affect.

[00:18:52.77] Now it seems to me a disturbing question and a very difficult question. I can state my views about the two extremes, but what happens in the middle between the two, I'm not so sure.

[00:19:05.35] I wonder-- if I may interrupt for a moment-- if we aren't talking, perhaps, about two different things. One of them is a kind of recognition in the poem of the things that are going on at the present time, taking cognizance of the issues of the day and incorporating them into the poetry--

[00:19:23.11] Yes.

[00:19:23.42] --but perhaps for the sake of the poem or because the poem means to reflect a life that is immediate. That's one thing. Another, perhaps, is hoping that the reader will be influenced to go out and do something on the basis of the poem. Are these things separable?

[00:19:39.87] Well, they are indeed separable. They should be separated. But when I said that "Burial Ground by the Ties" seems to have behind it a desire that minds should be changed, I didn't mean necessarily a desire that anyone should go out and carry through a political action of some kind, but rather a desire that one's feeling about human beings should change. After all, the various racial groups who came into this country and many of whom gave their lives for the construction of the basic economy of the country hadn't had down to that time, except in the rather general words of Whitman, very much recognition, that is their actions and their services haven't been recognized. And what this poem does clearly seem to me now reading it to hope is that a different feeling about the people who built the railroads, the people who drove the great routes through the continent might follow so that it lies a halfway between these.

[00:20:44.89] Since you yourself have, you might say, worked in both strains-- I don't know that they can be separated into two strains. But you have done the first poem that we heard you read, and then you have done this rather different kind of second poem-- when you are first thinking of a poem-- or whatever word should be used. I don't know-- how do you come to it? Or how does it come to you? Does it come to you from the point of view of this action or this embracing of contemporary life? Does it come to you in terms of the still image, the first thing we talked about? How do you approach a poem when you're first beginning to wrestle with it.

[00:21:19.01] I would think in neither of these ways. This is a difficult thing, of course, to talk about, because one rarely catches oneself at it.

[00:21:26.10] Which comes first, the chicken or the egg?

[00:21:27.72] One rarely catches oneself at it. But I suspect that what moves one always is some sort of perception, and a perception, since it's art we're talking about, of a sensuous nature, that is a perception of some figured thing that has significance and meaning, that one begins with that. And this, perhaps-- and perhaps this is what you asked the question-- is very relevant to the matter of poetry used as propaganda, where certainly a man starts with a purpose in mind and then gives it musculature and bones and it works it up and says, all right, now go out and fight my battle for me. But poetry isn't written that way.

[00:22:10.53] I would suppose that the other observation you made is the real answer to it. A man not only may, it would seem to me he necessarily must, use the world in which he lives, use the people he sees, use what happens to him, his experience-- after all, what else has he?-- as the substance and fabric of his poetry. And if doesn't use that, if his poetry doesn't come out of that, it will be merely literary.

[00:22:37.89] Now you're engaged actively in the teaching of poetry. You've been engaged in what from time to time has been a quarrel over the purposes of poetry and the nature of poetry. Do you detect in, let's say, your students at the present time or in the young men are just beginning to write verse any new tendency at all, any new balance of these factors?

[00:23:02.94] I certainly do among students. Not balancing, but a new tendency, an interesting tendency, an inward turning of the inquiring mind and an inward turning of interest, a turning inward upon the emotional life and upon spiritual life.

[00:23:25.72] The point that I would like to make, however, is that this shift in, it's not so much point of view as orientation, perspective, doesn't really mean that the problem that you and I have been talking about has now ceased to exist. It can exist quite as much inwardly as outwardly. One isn't so apt to find poetry used for propaganda inwardly, but certainly one can find poetry immersed in the time, immersed in the life of the time inwardly quite as well as outwardly. So the problem remains, for me, a problem-- well, again, if you'll let me, I'd like to read a poem in which I tried at least to state what the nature of the choice seems to me to be.

[00:24:10.33] I think I know the name of the poem. "Calypso's Island?"

[00:24:12.14] Yeah, "Calypso's Island." It deals, of course, with that incident in the wanderings of Odysseus when, after a blessed year on this blessed island where in the arms of the fairest of immortals he was himself sure of immortality, he nevertheless insisted on going back to the sea, going back to his ship, and back to his aging wife.

[00:24:36.68] Mm hmm.

[00:24:39.95] "Calypso's Island." "I know very well, Goddess, she is not beautiful as you are, could not be. She is a woman, mortal, subject to the chances, duty of childbed, sorrow that changes cheeks, the tomb, for unlike you, she will grow gray, grow older, gray and older, sleep in that small room. She is not beautiful as you, oh, Golden. You are immortal and will never change and can make me immortal also, fold your garment round me, make me whole and strange as those who live forever, not the while that we live, keep me from those dogging dangers, ships and the wars, in this green far-off island, silent of all but sea's eternal sound or sea-pines when the lull of surf is silent.

[00:25:33.46] Goddess, I know how excellent this ground, what charmed contentment of the removed heart the bees make in the lavender, where pounding surf sounds far off and the bird that darts darts through its own eternity of overnight light, motionless in motion, and the startled hair is startled into stone, the fly forever golden in the flickering glance of leafy sunlight that still holds it. I know you, Goddess, and your caves that answer ocean's confused voices with a voice, you poplars where the storms are turned to dances, arms where the heart is turned. You give the choice to hold forever what forever passes, to hide from what will pass forever.

[00:26:22.89] Moist, moist are your well stones, Goddess, cool your grasses. And she, she is a woman with that fault of change that will be death in her at last. Nevertheless, I long for the cold salt restless, contending sea and for the island where the grass dies and the seasons alter where that one wears the sunlight for a while."

[00:26:52.71] What I think you see is that lovely as the island is and beautiful as it would be to live on it forever, one must leave it, one must return to life, or the island won't be there any longer.

[00:27:07.23] The contending sea is the working phrase here.

[00:27:10.43] The contending sea is the working phrase.

[00:27:12.10] Right.

[00:27:12.65] And one must return into life. There is nothing human that isn't relevant to the art of poetry, nothing human that doesn't belong to the poet. Keats' belief in the holiness of the heart's affections is really the key to poet and poetry. And the answer to this dilemma is the human answer.

[00:27:35.80] I see. We've been talking with Mr. Archibald MacLeish about the nature of poetry and the nature of the act of writing poetry. And Mr. MacLeish does not believe that the poem can be allowed to stand simply as a beautiful object frozen in time. It is that, but it's something else too. In addition to being an object, it's also action, and it reaches out to embrace the activities of the human mind and heart.

Distributor: Icarus Films

Length: 30 minutes

Date: 1991

Genre: Interview

Language: English

Grade: 10-12, College, Adult

Color/BW:

Closed Captioning: Available

Interactive Transcript: Available

Existing customers, please log in to view this film.

New to Docuseek? Register to request a quote.